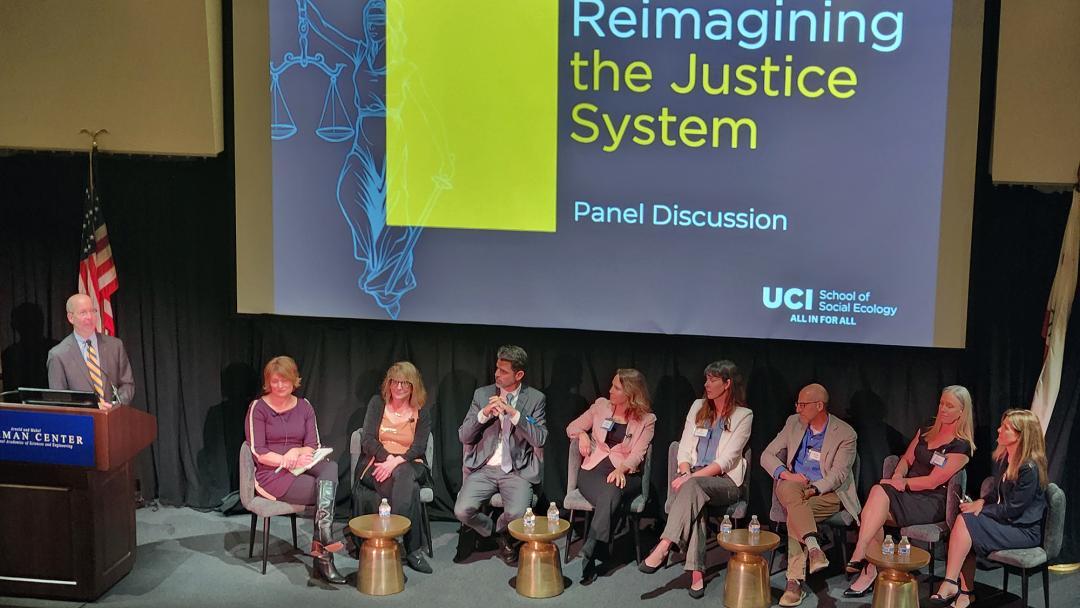

From left: Jon Gould, Candice Odgers, Elizabeth Loftus, Nicholas Scurich, Charis Kubrin, J. Zoe Klemfuss, Simon Cole, Jodi Quas and Elizabeth Cauffman.

Event, hosted by Distinguished Professor Loftus, promotes standing by science

Science has the power to change the world for the better. That was the message at the School of Social Ecology’s recent “Reimagining the Justice System” panel discussion.

Elizabeth Loftus, distinguished professor of psychological science and criminology, law & society, who made the event possible through the donation of her American Philosophical Society Patrick Suppes Prize money, kicked off the discussion by talking about the wrongful conviction of a man who was accused of raping a woman in 1984.

Elizabeth Loftus, distinguished professor of psychological science and criminology, law & society, who made the event possible through the donation of her American Philosophical Society Patrick Suppes Prize money, kicked off the discussion by talking about the wrongful conviction of a man who was accused of raping a woman in 1984.

“Jennifer Thompson was a college student in North Carolina when she was viciously raped,” Loftus said. “She went to a line-up and identified a man named Ronald Cotton as her rapist and she was a very compelling witness, very convincing, very articulate, very believable, and the jury quickly convicted Ronald of this crime. Years later, while he was in prison, DNA testing was done and it was revealed that another man, named Bobby Poole, was actually the person who committed the rape. Jennifer felt horrible, but what makes this case different from one more case of a wrongful conviction involving a rape, a white victim and an African American man is that these two people ended up meeting and they became friends and they started going around the country, advocating for reforms in the legal system to prevent future injustice.”

One of the most common reasons for wrongful convictions is faulty human memory, according to Loftus, who has been studying memory for 50 years. She tells her students about cases like Cotton’s to impress upon them the importance of human memory research.

Her work aims to make a difference in the justice system. And, six of Loftus’ UC Irvine colleagues — Elizabeth Cauffman, J. Zoe Klemfuss, Jodi Quas and Nicholas Scurich, psychological science faculty members; and Simon Cole and Charis Kubrin, criminology, law & society faculty members, who all do research on topics that can affect change in the criminal justice and legal system — spoke about their work’s impact. The discussion was moderated by Candice Odgers, director of research and faculty development and professor of psychological science.

Because their work centers on exposing problems in the criminal justice system, it takes courage to stand behind the science, Dean Jon Gould said. “There is a price that scientists pay at times for doing research that matters.”

If something goes awry when you’re in a hospital, he said, “there is a convening of doctors to talk about what happened to try to improve it. But, in the criminal justice system, the area of society where the state is using its most penal power, we don’t have that. The system, oftentimes, likes to pretend that it's infallible and that we don’t need to do anything to improve it.”

What the panelists are showing, Gould continued, “is that there are some problems in the justice system. This is a group of scholars saying that if there’s a problem, there’s a solution and if there’s a solution, I want to be part of that.”

The scholars agreed.

“One reason I love being a professor in the School of Social Ecology is its recognition — indeed embodiment — of the principle that science should drive solutions, echoing my belief in the importance of public criminology,” said Kubrin, who researches the use of rap lyrics as evidence in criminal trials, or what she calls “Rap on Trial.” “I’ve long wondered: How can my research make a difference?”

One way she is doing so is by leading workshops and training sessions for public defenders involved in “Rap on Trial” cases. She also co-authored a legal guide that serves as a resource for attorneys dealing with rap evidence. The guide provides explanations of rap conventions that may be unfamiliar to courtroom actors, an overview of experimental research on rap and bias, legal grounds for evidentiary and First Amendment challenges to admitting lyrics into trial, and more.

Kubrin’s research findings even helped provide the impetus for California’s AB 2799, the Decriminalizing Creative Expression Act of 2022 — the nation’s first-ever legislation to place guardrails on the use of rap lyrics in criminal proceedings.

Scurich’s research has been cited by the Supreme Court of the United States. His expertise is in psychology and law, judgment and decision making and violence risk assessment. He spoke on flawed forensics around firearm identification.

Klemfuss’ research, which focuses on how children remember and report about their past experiences, has direct application in legal settings where a child’s memory may be the deciding evidence in a case.

During the 1980s, when hundreds of children were led to make false accusations of physical and sexual abuse in the McMartin Preschool case, there were no clear empirical guidelines about how to appropriately interview child witnesses, Klemfuss said.

Today, guidelines are being established and improved. And, Klemfuss’ lab is contributing through research on how best practice forensic interviewing should look.

She uses automated facial recognition software to look at real-time emotion expression of interviewers and how it maps onto children’s emotion expression and how they respond. She also collects physiological measures, such as heart rate and salivary cortisol, of children’s stress responses during interviews. Her evidence shows that keeping questions short and as open-ended as possible and using age-appropriate terms and concepts produces the most accurate testimony.

“We’ve come a long way from the McMartin case, but we still have a lot of work to do,” Klemfuss said. “Very young children can provide reliable evidence, but it is up to us to make sure that they are able to do so.”

Cole, director of the National Registry of Exonerations, said people used to think that wrongful convictions never happened.

“DNA exonerations changed all that but not all exonerations are DNA exonerations,” he said, adding that the NRE is a living archive, keeping track of all exonerations in the country.

“We’ve counted more than 3,400 since 1989,” he said. “We do social science coding and analysis of every case because every story counts.”

Each case is documented in the registry and the hope, Cole said, is to see it drive policy reform regarding things such as better procedures for forensic science, eye witness interrogations and procedures.

Along that vein, Quas spoke about young victims of human trafficking. Her research focuses on how victims are questioned by authorities, how they respond and, more importantly, how to improve the interrogation procedures to ensure that the victims are identified and protected and traffickers are prosecuted.

Quas and her research team has analyzed recordings of human trafficking victim interviews by local police and officials from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and found that the majority of their questions are leading or closed and their environment is cold and formal, which can be problematic.

In such situations, teens often do not respond well.

“They’re teens. They’re evasive,” Quas said. “They’re sassy. They’re usually fairly unhelpful. So, what do we do, how do we reimagine justice?”

Among solutions: Quas offers best interview practice tips such as asking open-ended questions in a warm and supportive environment. She also trains police and other investigators, school officials and healthcare workers on adolescent development on identifying sex trafficking victims.

“Our hope is to promote positive youth development for all adolescents, particularly those who are vulnerable,” Quas said.

Science is the way to do that, said Cauffman, who spoke about the Orange County Young Adult Court that she co-created. “We can use science to help guide how we change the system. That’s exactly what we do here in Orange County with the Young Adult Court.”

It is a collaborative court for first-time felony offenders between the ages of 18 and 25. Participants who complete the two-year program can have their felony charge reduced or dismissed. The program consists of developing a “youth action plan,” which lays out all the steps participants must complete such as attending all court hearings, meeting with probation officers and case managers, getting substance and/or alcohol abuse treatment, mental health counseling, employment and education advice and following through.

“We have an opportunity to change how young people are treated in the system and, ultimately, how we treat them in society,” Cauffman said.

Now, back to memory.

“Just because somebody tells you something and they say it with a whole lot of confidence, and they describe it in a lot of detail, and they cry when they tell you the story, it doesn’t mean that it actually happened that way,” Loftus said. “You need external corroboration to know whether you're dealing with an authentic memory or one that’s a product of some other process and such a realization might have made a difference for people like Ronald Cotton.”

About 200 people attended the panel discussion and walked away in awe. One retired professor of computer sciences, who attended with her husband and a couple of UCLA faculty members, noted that she came away “extremely impressed. Not only was the program interesting and exciting and full of energy, but the faculty you have gathered at the School of Social Ecology is quite spectacular! It is a wonderful credit to Beth Loftus that so many young faculty adopted her style of taking science to where it matters.”